|

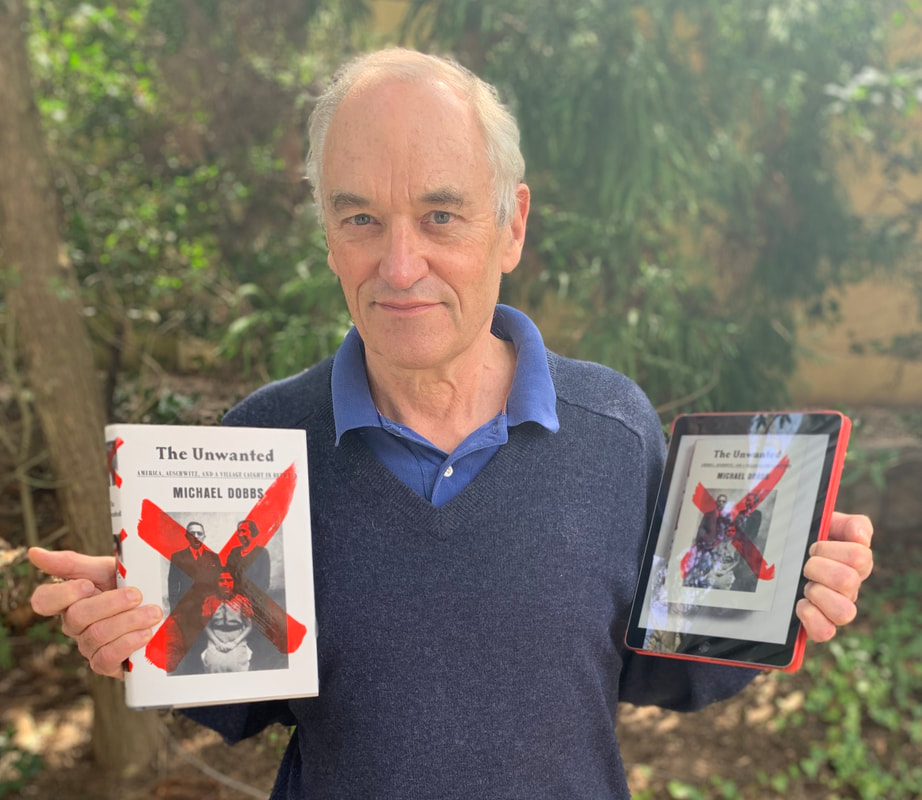

Even for the author of six books, there is still something magical about holding the finished product in your hands for the very first time. Today, I received advance copies of my latest opus, The Unwanted: America, Auschwitz, and a Village Caught in Between, which will be released on April 2. I hope you will agree that the publisher, Knopf, has done an exceptional job. This may be a slight exaggeration, but I think of Knopf (founded by Alfred A. Knopf and his wife Blanche in 1915) as the last of America’s “gentleman publishers.” They are a throwback to the age when editors treated writers with enormous courtesy, inviting them to long lunches and tolerating multi-year delays in the submission of manuscripts. They are also renowned for their gorgeously produced books. Even though Knopf is now part of a German-owned conglomerate, a Knopf book includes a number of design features, such as rough deckle edges and high quality paper, that make it easily recognizable. This time, as a special treat, I had the opportunity to see my book roll off the presses. Knopf books are printed in a small town in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia called Berryville, an hour’s drive from Washington D.C. where I live. It turns out that this charming, but otherwise insignificant town (population 4,185) is the location of one the largest printing operations in the United States, producing more than 10 million books a month. When I arrived, high-speed offset presses were churning out yet another reprint of Michelle Obama’s autobiography, Becoming, which has already sold some five million copies in the U.S. alone. In a different corner of the plant, my book was being printed in 32-page sections, known as “signatures,” which are most suitable for binding. In the photograph below, you can see the proud author holding a completed signature of The Unwanted, while a worker throws slightly imperfect versions into the trash. My main takeaway from my visit to Berryville was how old-fashioned the printing process remains. For all the technological advances of recent years, the basic techniques of book production are essentially little changed from the days of Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century. Ink is smeared onto paper through a mechanized process, and then bound into books with covers made out of pressed cardboard. The typefaces used in my book were designed by a Dutchman in the 17th century.

Like many of you, I suspect, I went through a phase of reading books on a Kindle or an I-Pad. But today, I greatly prefer the tactile sensation of handling a physical book. After many hours gazing into computer screens and smart phones, it is much more relaxing to curl up with a beautifully produced book than yet another electronic device. It is also much easier to move back and forth in a book, consulting an endnote or refreshing your memory about a character who has appeared in an earlier chapter. Six hundred years after its invention, the physical book is not only competitive with any of our modern technologies. With the possible exception of portability, it is superior in nearly every respect. In an age of bewildering change, that is immensely reassuring.

2 Comments

Geoffery Dobbs

3/19/2019 11:52:22 am

Might be about time for you to write my biography

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About MichaelMichael Dobbs is the author of seven books, including the best-selling One Minute to Midnight. His latest book, King Richard, is about Nixon and Watergate. Archives

June 2021

|