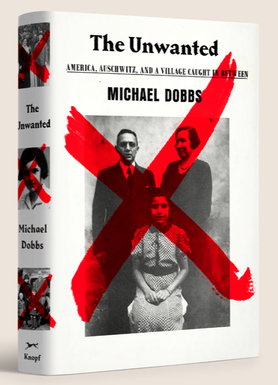

My latest book, The Unwanted, will be published on April 2. It is about the life-or-death struggle of Jews fleeing Nazi persecution to obtain a safe haven across the ocean. In order to emphasize the human drama, I focus on the fates of Jewish families from a single village on the edge of the Black Forest, in southwestern Germany. The overarching story line is tragically simple: the people featured in the book either get to America or they perish in Auschwitz. In the process of telling their stories, I examine the reasons why they ended up where they did, which are connected to the U.S. immigration policy of the time. Having now written six books, this seems a good opportunity to reflect on my writing methods and sources of inspiration. Needless to say, I have been greatly influenced by other books and other writers. I agree with the advice given to aspiring writers by the thriller novelist Steven King in his now classic On Writing. “If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot.” You might think that, as a non-fiction writer, I would read primarily non-fiction, but this is not the case. Most of my reading, particularly when I am in search of literary models, is fiction. My reading list during the two years that I researched and wrote The Unwanted is full of the great nineteenth century novelists like Charlotte Bronte, Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, and Anthony Trollope (a recent, unexpected pleasure). It includes twentieth century writers who have stood the test of time (Evelyn Waugh, George Orwell, Ernest Hemingway, Nancy Mitford, C.S. Forester, Wilkie Collins, Laurence Durrell, Eric Ambler), and a sprinkling of modern novelists (John Le Carré, Robert Harris, Alan Furst, Ken Follett, John Grisham.) It is not that I have stopped reading non-fiction entirely. As I worked on The Unwanted, I consulted many histories of the period leading up to the Holocaust, and even read a few of them cover-to-cover. One book I found particularly helpful was The Pity of It All by Amos Elon, which looks at the Jewish experience in Germany over two centuries, up to Hitler’s assumption of power in 1933. I was captivated by Varian Fry’s lively memoir, Surrender on Demand, describing his experiences in unoccupied France between 1940 and 1941 rescuing intellectuals, artists, and other public figures on the run from Hitler. For the most part, however, I read (or perused) histories of the period mainly for research purposes rather than for enjoyment. As guides on how to write a compelling narrative, I looked elsewhere. If there is a single book that I used as a model for The Unwanted, it is probably A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. Just as Dickens draws an unforgettable portrait of a city caught up in the turmoil of revolution (Paris), juxtaposed with a city of relative calm and prosperity (London), I was interested in the contrast between a continent at war (Europe) and a continent at peace (America). I considered A Tale of Two Continents as a possible title for my book but discarded it in favor of The Unwanted in order to focus on the people seeking refuge. But I pay homage to Dickens with a quote at the very beginning of the book, “It was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way.” A now almost forgotten novel that helped me get a feel for the nightmarish refugee experience in Europe resulting from the rise of Hitler was Transit by Anna Seghers. Herself a refugee from Nazism, Seghers provides a vivid account of the bureaucratic maze that confronted refugees as they ran from one consulate to another in pursuit of the rubber stamps and documents that would save their lives. Much of her novel is set in Marseille, the great port on the Mediterranean that is also the transit city for some of the characters in my book. I cite her descriptions of the stone-faced consuls “who make you feel as if you’re nothing” and the “frizzy-haired bureaucratic goblins” of the French police, with their passion for “sorting, classifying, registering, and stamping” the desperate people passing through their doors. One of the kindest reviews I have ever received, for my book One Minute to Midnight on the Cuban missile crisis, compared my writing style to John le Carré and Alan Furst, two novelists I greatly admire. In emulating some of their techniques, I understand of course that non-fiction writers are different from writers of fiction in one crucial, very obvious, respect: We are not allowed to make anything up! This raises some interesting questions about the boundaries and overlap between fiction and non-fiction that I intend to explore in a series of future blog posts.

3 Comments

|

About MichaelMichael Dobbs is the author of seven books, including the best-selling One Minute to Midnight. His latest book, King Richard, is about Nixon and Watergate. Archives

June 2021

|