|

Destruction of Kippenheim synagogue, November 10, 1938 With a new book coming out in April, I wanted to share some thoughts on the art of historical narrative. As I mentioned in my last blog post, I believe that the methods of fiction can be applied to non-fiction with one very large caveat: you can’t make anything up. The number one lesson that I take away from the writers I admire--whether they are novelists or historians--is to immerse the reader as deeply as possible in the story that I am telling and the times I am writing about.

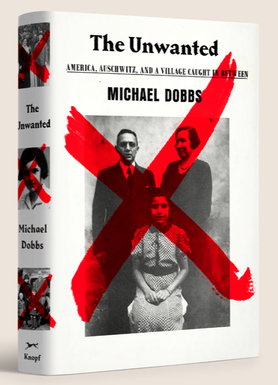

I am a traditionalist when it comes to the principles of story-telling. I prefer to read (and write) history books with a clear beginning, middle, and end. The plot should unfold naturally and sequentially, building to a culminating point in the narrative, when the dilemmas confronting your characters are somehow resolved, either happily or tragically. Subtle foreshadowing (viz. the gun on the wall in the first act of a Chekhov play) is permissible, but the author must never get ahead of the story he or she is telling. It seems hardly coincidental that the most successful of our modern-day historians are also accomplished writers who know how to construct a powerful narrative. My personal role models include David McCullough and Edmund Morris (for his three-part Theodore Roosevelt biography, not the partly-fictionalized biography of Ronald Reagan). Both McCullough and Morris are adept at keeping their stories moving forward, weaving necessary background into the narrative without slowing it down. The trouble with history, of course, is that we typically know how the story ends, in contrast to novels, where the suspense is maintained until the very last moment. There is no mystery about who won World War II or what happened to the Soviet Union. To draw on the plot of one of my previous books, One Minute to Midnight, we know very well that the world did not come to an end in October 1962. You might think this would remove much of the suspense from the story of the Cuban missile crisis but this was not the case in my experience. The excitement derives not from how the story ends, but from the twists and turns along the way. One of my favorite historians, Barbara Tuchman, described this phenomenon well in her essay, In Search of History. Initially, she worried “a good deal” about the “the problem of keeping up suspense in a narrative whose outcome is known.” After a while, she discovered that the problem resolved itself. “If one writes as of the time, without using the benefit of hindsight, resisting always the temptation to refer to events still ahead, the suspense will build itself up naturally.” She cites the example of Marshal Joffre hesitating before the Battle of the Marne in 1914, when the French army prevented the Germans from marching on Paris. Even though the result of the battle is well known, the suspense becomes “almost unbearable, because one knows that if he had made the wrong decision, you and I might not be here today.” Another good example is Frederick Forsyth’s thriller novel, The Day of the Jackal, which describes the attempted assassination of Charles de Gaulle. Anyone even vaguely familiar with modern French history knows very well that the plot fails and General de Gaulle survives. Nevertheless, Forsyth engrosses us so completely in his meticulous descriptions of the assassin’s preparations that we keep turning the pages to find out what goes wrong. In addition to maintaining suspense, the narrative method sidesteps the curse of omniscient hindsight, an affliction of many historians. This is particularly acute with shattering events such as the Holocaust that have colored our entire understanding of 20th century history. We should resist the temptation to project out current-day knowledge backwards when examining the choices made by politicians before the annihilation of six million Jews. While we can certainly criticize the failure of Franklin Roosevelt and other American leaders to do more to assist refugees fleeing from Hitler, it is unfair to paint them as complicit in events that had not yet taken place. The nineteenth century Danish philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, once observed that history is “lived forwards” but “understood backwards.” Historians like to find order, logic, and inevitability in events that sometimes defy coherent and logical explanation. One way to correct this bias is to relate historical events as they happened, from the point of view of the people who lived through them. By telling the story forwards (as experienced) rather than backwards (as now understood), we can re-create its cliff-hanging excitement and unpredictability. We also gain new insights into the actions and motivations of the principal players. That, at least, has been the philosophy that has guided me through the writing of six non-fiction books. In my latest book, The Unwanted, I tell the story of a group of German Jews attempting to flee Nazi persecution. The opening scene describes the shattering events of Kristallnacht, on November 10, 1938, in a village on the edge of the Black Forest. (See photograph above.) This is the moment when the Jews of Kippenheim realize that there is no alternative to emigration from Germany if they are to survive. Their preferred destination is the United States, although they are willing to settle for other places of refuge. In keeping with Barbara Tuchman’s advice, I resist the temptation to jump forward to events that have not yet happened. Instead I recount, as accurately and vividly as possible, the various obstacles they encounter and their frantic efforts to overcome them. Intertwined with the story of the refugees is the story of U.S. immigration policy under Roosevelt.The tension builds naturally as the families with whom we become acquainted in the opening chapter organize their attempted escapes from Europe. Some of them make it to the promised land across the ocean. Others end up in Auschwitz, their applications for American visas “still pending.” I hope you find the story as alternately inspiring, heart-breaking, and exciting as I did, when I researched and wrote it.

2 Comments

My latest book, The Unwanted, will be published on April 2. It is about the life-or-death struggle of Jews fleeing Nazi persecution to obtain a safe haven across the ocean. In order to emphasize the human drama, I focus on the fates of Jewish families from a single village on the edge of the Black Forest, in southwestern Germany. The overarching story line is tragically simple: the people featured in the book either get to America or they perish in Auschwitz. In the process of telling their stories, I examine the reasons why they ended up where they did, which are connected to the U.S. immigration policy of the time. Having now written six books, this seems a good opportunity to reflect on my writing methods and sources of inspiration. Needless to say, I have been greatly influenced by other books and other writers. I agree with the advice given to aspiring writers by the thriller novelist Steven King in his now classic On Writing. “If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot.” You might think that, as a non-fiction writer, I would read primarily non-fiction, but this is not the case. Most of my reading, particularly when I am in search of literary models, is fiction. My reading list during the two years that I researched and wrote The Unwanted is full of the great nineteenth century novelists like Charlotte Bronte, Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, and Anthony Trollope (a recent, unexpected pleasure). It includes twentieth century writers who have stood the test of time (Evelyn Waugh, George Orwell, Ernest Hemingway, Nancy Mitford, C.S. Forester, Wilkie Collins, Laurence Durrell, Eric Ambler), and a sprinkling of modern novelists (John Le Carré, Robert Harris, Alan Furst, Ken Follett, John Grisham.) It is not that I have stopped reading non-fiction entirely. As I worked on The Unwanted, I consulted many histories of the period leading up to the Holocaust, and even read a few of them cover-to-cover. One book I found particularly helpful was The Pity of It All by Amos Elon, which looks at the Jewish experience in Germany over two centuries, up to Hitler’s assumption of power in 1933. I was captivated by Varian Fry’s lively memoir, Surrender on Demand, describing his experiences in unoccupied France between 1940 and 1941 rescuing intellectuals, artists, and other public figures on the run from Hitler. For the most part, however, I read (or perused) histories of the period mainly for research purposes rather than for enjoyment. As guides on how to write a compelling narrative, I looked elsewhere. If there is a single book that I used as a model for The Unwanted, it is probably A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. Just as Dickens draws an unforgettable portrait of a city caught up in the turmoil of revolution (Paris), juxtaposed with a city of relative calm and prosperity (London), I was interested in the contrast between a continent at war (Europe) and a continent at peace (America). I considered A Tale of Two Continents as a possible title for my book but discarded it in favor of The Unwanted in order to focus on the people seeking refuge. But I pay homage to Dickens with a quote at the very beginning of the book, “It was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way.” A now almost forgotten novel that helped me get a feel for the nightmarish refugee experience in Europe resulting from the rise of Hitler was Transit by Anna Seghers. Herself a refugee from Nazism, Seghers provides a vivid account of the bureaucratic maze that confronted refugees as they ran from one consulate to another in pursuit of the rubber stamps and documents that would save their lives. Much of her novel is set in Marseille, the great port on the Mediterranean that is also the transit city for some of the characters in my book. I cite her descriptions of the stone-faced consuls “who make you feel as if you’re nothing” and the “frizzy-haired bureaucratic goblins” of the French police, with their passion for “sorting, classifying, registering, and stamping” the desperate people passing through their doors. One of the kindest reviews I have ever received, for my book One Minute to Midnight on the Cuban missile crisis, compared my writing style to John le Carré and Alan Furst, two novelists I greatly admire. In emulating some of their techniques, I understand of course that non-fiction writers are different from writers of fiction in one crucial, very obvious, respect: We are not allowed to make anything up! This raises some interesting questions about the boundaries and overlap between fiction and non-fiction that I intend to explore in a series of future blog posts. We all know when the Cold War ended: with the fall of the Berlin wall in November 1989. When it began is much more controversial. In my new book, Six Months in 1945, I say that it began in the six month period between the Yalta conference in February 1945 and the bombing of Hiroshima in August 1945. I also argue that it was the inevitable outgrowth of World War II. When Americans and Russians met in the heart of Europe in April 1945, they turned, almost overnight, from World War II allies into Cold War rivals.

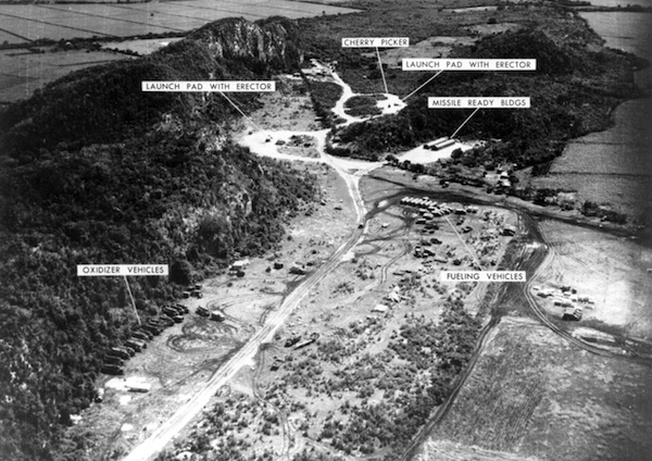

For more on my reasoning, and why I differ with other historians, see an article that I just wrote for the History News Network. And, of course, read my book!  I have been invited to numerous events commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Cuban missile crisis, the subject of my book, One Minute to Midnight. The invitation that gave me most pleasure, however, was to be asked to address 500 photo intelligence analysts from the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency. I was joined on stage by two of the analysts who discovered the Soviet missiles back in October 1962, Dino Brugioni and Vincent DiRenzo. I was tell them what they missed back in 1962. The president kept on asking them "Where are the nuclear warheads?" but they were never able to answer that question conclusively. In One Minute to Midnight, I solve this mystery, identifying the nuclear warhead bunker near Bejucal where the warheads were stored. Of course I had one big advantage that the intelligence analysts did not enjoy at the time. Writing about the missile crisis nearly half a century later, I was able to talk to Soviet veterans who had responsibility for looking after the nuclear warheads. Hindsight is a wonderful thing! My latest book, Six Months in 1945, is out today! It tells the story of the beginning of early days of the Cold War, how Americans and Russians met each other in the heart of Europe and decided that they didn't like each other after all. In the space of just six months, the U.S. and the Soviet Union went from being WWII allies to Cold War rivals.

By coincidence, this is the day the "Thirteen Days" began ticking in the Cuban missile crisis, when JFK was told about the presence of Soviet missiles on Cuba ln October 16,1962. I punctuate some of the mythology surrounding the crisis in a piece for the New York Times here. I make the point that our political leaders learned the wrong lessons from the crisis, and got into unnecessary wars in Vietnam and Iraq. Having just completed a trilogy of books about decisive moments in the Cold War, I am bemused by the "Who lost the Arab Spring?" debate that suddenly seems to be gripping Washington. Like many foreign policy controversies, this one is driven more by the domestic political agenda -- and specifically the presidential election in November -- than informed analysis of actual events.

To hear many Republicans talk, Barack Obama is to blame for the sudden upsurge of violence in the Arab world that claimed the life of our brave ambassador to Libya. The president's repeated "apologies" for American values have encouraged the extremists in Cairo, Benghazi, and elsewhere. This kind of argument is similar to the "Who lost China?" debate that followed the Chinese Communist seizure of power in 1949. It supposes that China -- or the Arab Spring, in this case -- was ours to lose. The reality, of course, is that a U.S. president has very little influence over what happens in the paddy-fields of China or the streets of Cairo or the bazaars of Baghdad, unless he chooses to send in the First Armored Division. And as we have seen in Iraq, the forceful exercise of presidential power does not always produce the desired results. A central theme of my three Cold War books -- Down with Big Brother, One Minute to Midnight, and Six Months in 1945 -- is the role of political leadership versus the chaotic forces of history. There are moments -- the Cuban missile crisis is a good example -- when the fate of the world hangs on the decisions and actions of a few individuals. More generally, however, the politicians are left scrambling to keep pace with events that are beyond their ability to control. The most successful leaders are those who understand this fundamental truth, but keep plugging away all the same. At the height of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln lamented that he did not control events. "Events control me." And yet he somehow steered the country through the greatest crisis in its history. JFK expressed very similar sentiments during the Cuban missile crisis. Of course, there are different types of foreign policy crises. As I describe in One Minute to Midnight, the missile crisis is a good example of a crisis that Kennedy and Khrushchev helped to create. This is a rare case where two men actually had the power to blow up the world. Through a series of mistakes and miscalculations, Kennedy and Khrushchev led the world to the brink of nuclear destruction -- but also had the wisdom to lead it back from the brink. The onset of the Cold War was a different kind of crisis, more akin to the kind of crisis we are facing in the Middle East right now. In my forthcoming book, Six Months in 1945, I conclude that neither FDR, nor Stalin, nor Churchill, nor Truman wanted the Cold War. They sought to postpone it, for as long as they could. But it happened anyway -- because of the larger forces of history identified by Alexis de Tocqueville more than a century before. "Their starting point is different and their courses are not the same," de Tocqueville wrote of Russia and America in 1839, "yet each of them seems marked out by the will of Heaven to sway the destinies of half the globe." I think we are seeing a historical upheaval of similar dimensions play out before our eyes on the streets of the Arab world. In my book One Minute to Midnight, I touch on a provocative question that relates to both the Cuban missile crisis and the run-up to the war in Iraq: Did the intelligence people tell the president what they thought he wanted to hear?

In some ways, the Cuban case was the mirror opposite of the Iraq case. In Iraq, the Bush administration were intent on showing that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction—and lo and behold, the CIA produced the “evidence,” much of it fabricated, that helped prove the case. In Cuba, the intelligence agency helped the Kennedy administration fend off Republican charges that it was turning a blind eye to the installation of nuclear weapons on Cuba. It was only on October 15—when it received incontrovertible photographic evidence of Soviet duplicity—that the agency finally reversed its estimate that the Soviet Union was not shipping nuclear missiles to Cuba. With congressional elections looming in November, President Kennedy succeeded in keeping a tight lid on any intelligence information that conflicted with the administration’s official position. After my book appeared in 2008, I had the opportunity to ask the then-CIA director, General Michael Hayden, about the politicization of intelligence, in both the Cuba and Iraq cases. Not surprisingly, he defended the honor of his agency. He attributed mistaken analysis not to political pressure, but to a very human tendency to pay too much attention to conventional wisdom. Explaining his point, he noted that the Soviets had never deployed nuclear missiles outside eastern Europe, prior to 1962. Analysts erroneously assumed that this status quo would continue to prevail. In the case of Iraq, analysts were swayed by the fact that Saddam Hussein did have a vigorous WMD program up until the first Gulf War in 1991. The analysts assumed that he was still developing WMD. I think there is some truth in this explanation, but believe that politicization was also a factor. Political interference with the intelligence community operates in subtle ways. The overwhelming majority of analysts at the working level are non-political and highly professional, but they are also attuned to the demands of their bosses. Information and analysis is selected and filtered as it passes upwards through the ranks. The desire to supply the White House with information that will help the president build a political case can generate misinformation. It is not only the American public that is fooled in such cases, it is also the commander-in-chief and his closest advisers. As Bobby Kennedy later remarked about the deployment of Soviet nuclear missiles to Cuba, “we had been fooled by Khrushchev, but we had also fooled ourselves.” Fifty years ago this month, an armada of Soviet ships crossed the Atlantic, headed toward Cuba. As this August 21 New York Times report shows, the Kennedy administration dismissed claims by Cuban exiles in Miami that the ships were carrying combat troops and sophisticated military equipment. U.S. officials were initially inclined to accept the Soviet explanation that most of the personnel arriving in Cuba were "civilian technicians," with a sprinkling of "military advisers."

As I describe in my book One Minute to Midnight, U.S. intelligence estimated Soviet troop strength in Cuba at between 4,000-4,500 as late as early October 1962, when by that time around 35,000 Soviet soldiers had arrived on the island. It was not until October 15 that the CIA figured out that these soldiers were equipped with nuclear weapons capable of destroying major American cities. One reason for the bungled CIA intelligence was that the Russians are very good at what they called maskirovka, the art of concealment. They dressed their soldiers up to look like "agricultural technicians," in conformity with the cover story. The CIA did not latch on to the fact that the "agricultural technicians" were all wearing almost identical checkered shirts-see photograph above-leading Soviet wags to call the Cuban adventure "Operation Checkered Shirt." But another reason for the miscalculation was the CIA's tendency to "mirror image." The intelligence analysts used American standards, rather than Russians standards, as the basis for measuring Soviet troop strength. They observed the number of Soviet ships crossing the Atlantic, figured out the likely deck space, and calculated the number of likely passengers. What they failed to understand was that the Russian soldiers were crammed below decks in almost slave transport conditions, with just sixteen square feet of living space per person, barely enough to lie down. There was one person in the CIA who correctly guessed the reason for the massive Soviet armada crossing the Atlantic-and that was the director, John McCone. Informed that the Soviets were developing a sophisticated air defense system in Cuba, McCone reasoned that they must have something very important to hide-and guessed that it was nuclear missiles. But this was an inspired deduction, not an intelligence estimate, and it did not represent the official position of the CIA. It should also be noted that McCone was the most senior Republican to serve in the Kennedy administration. His conclusions were politically embarrassing to the president, who was acutely aware of the approach of mid-term elections. In my next post, I will address a politically sensitive question that was raised again, four decades later, during the run-up to the Iraq War. Did the intelligence people tell the president what they thought he wanted to hear? I have posted a Q and A describing how I came to write my new book, Six Months in 1945. Key quote: "I am interested in hinge moments in history." You can read it here.

I am not the kind of writer who derives pleasure from the physical act of writing. When I sit down in front of my computer screen (I rarely write in any other way) I waste a lot of time procrastinating. I stare out the window, surf the Internet, fetch myself another glass of orange juice, anything to postpone the dreaded task of actually writing.

So why do I write? The obvious answer is that it is the way I earn a living. The more elevated explanation is that writing helps me to think—and is the way I best communicate, not only with other people, but also with myself. Writing is the way I organize and refine my ideas about a subject I have researched as a historian or witnessed as a journalist. It is not until I hammer out the words on the keyboard that I see everything in context and test the theories that have been spinning around in my head. It is at this moment that I pull the results of my research together and form them into a coherent narrative. A good example is my forthcoming book, Six Months in 1945, on the period between the Yalta conference and the bombing of Hiroshima. The physical act of writing forced me to make sense of the bewildering rush of events that accompanied the fall of Nazi Germany and the fateful encounter of America and Russia, in the heart of Europe. It was then that I understood that the Cold War actually began during this six-month period, despite the best intentions of the principals (FDR, Stalin, Churchill, and Truman.) Above all, writing is a miraculous form of communication. One of my journalistic role models when I started out was the British reporter Nicholas Tomalin, who was killed by a Syrian rocket during the 1973 Yom Kippur war. Tomalin defined the reporter’s “required talent” as the “creation of interest,” explaining that a journalist “takes a dull, or specialist, or esoteric situation, and makes newspaper readers want to know about it.” Unlike university professors, journalists do not have a captive audience. We know we have to work hard to capture, and retain, an audience. The trick, of course, is to do this without distorting the facts, and educate rather than titillate. It is tempting to try to create interest by hyping the story, filling your writing with superlatives such as “first,” “greatest,” “unprecedented,” ignoring the nuances that complicate the story. But it is much more satisfying to share the subtleties and complications with your readers. It is precisely the evidence that does not fit into the pre-cooked formulas that makes the research and writing process so interesting and rewarding. In some ways, I find writing history books easier than daily journalism. This may be because I feel less constrained by the conventions of the trade, and am not looking over my shoulder so much. I like to tell stories with vivid characters, exotic locales, and an exciting, well-defined plot. They must also have a clear beginning, middle, and end. Academics can be condescending about narrative history, but I find that telling the story in chronological fashion is the best way to explain what actually happened—and to keep your readers turning the page which is, after all, the point of the entire exercise. (Originally appeared in Publishers Weekly, August 17 2012.) |

About MichaelMichael Dobbs is the author of seven books, including the best-selling One Minute to Midnight. His latest book, King Richard, is about Nixon and Watergate. Archives

June 2021

|