|

I just finished "Homage to Catalonia," George Orwell's account of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, fighting on the Republican side. I earlier read another Spanish Civil War classic, "For Whom the Bell Tolls," by Ernest Hemingway. What impressed me about both these books--and what has given them their enduring value--is the willingness of both authors to include details and stories that are deeply discomforting to their own side. Both Orwell and Hemingway retained their critical eye and commitment to the truth in some of the most difficult circumstances imaginable, in the middle of a battle.

While both authors draw on their own personal experience, their perspective is very different. "For Whom the Bell Tolls" is a novel, told in the third person, through the eyes of an American participant. The protagonist, Robert Jordan, describes terrible atrocities committed by both sides in the service of a "higher cause." "Homage to Catalonia" is non-fiction, told in the first person, through Orwell's own eyes. In addition to his own time at the front, mainly waiting around in the mud and the cold for something to happen, he also describes the fratricidal fighting in Barcelona between the Communists and Anarchists/Trotskyists. His account of the revolution turning on itself, and devouring the original revolutionaries, prefigures his later masterpieces "Animal Farm" and "1984." As in these later books, Orwell describes a post-fact society, in which "truth" is determined by the political needs of the ruling party. Some quotes from Orwell's book that seem particularly pertinent today:

Having visited Barcelona, and taken the obligatory Gaudi tour, I was amused by Orwell's description of the Sagrada Familia cathedral (see photo above) as "one of the most hideous buildings in the world." Still unfinished eighty years later, Gaudi's masterpiece was one of the few churches in Barcelona that was not damaged during the revolution, spared because of its alleged "artistic value." Comments Orwell sourly: "I think the Anarchists showed bad taste in not blowing it up when they had the chance." Which just goes to prove that, when it comes to opinions about art, there really is no such thing as "the truth."

0 Comments

A grand old institution and independent book store, Politics and Prose has become THE place in Washington, if not the United States, for an author to launch a new book. I was delighted to join journalist Garrett Graff (whose own Watergate book will be published in November this year) for a conversation about King Richard. I have been on a Churchill binge recently. I have just finished The Splendid and the Vile by Erik Larson. Before that, I read the definitive Andrew Roberts biography Churchill: Walking with Destiny and Hero of the Empire about Churchill's time in South Africa by Candice Millard. Churchill is a gift to any halfway decent writer, as I discovered in writing my book about the end of World War II, Six Months in 1945: FDR, Stalin, Churchill, and Truman--from World War to Cold War. He is so colorful that it is hard not to make him interesting.

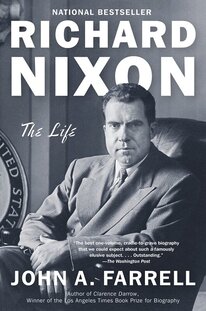

What sets Larson's book apart from others on the Blitz, and the first year of Churchill's premiership, is that he has skillfully weaved in the stories of other, lesser known characters, such as John Colville, his private secretary, and Mary Churchill, his daughter, into the narrative. In doing so, Larson not only tells a wonderful story, he makes the point that history is not just about the great and the powerful. In the shadow of history-making characters like Churchill and Roosevelt and Hitler and Stalin, ordinary life continues. People fall in love, struggle with their own personal demons, are happy or unhappy, laugh and cry. Tolstoy understood this too, of course: it's pretty much the same formula he uses in War and Peace. It's also a formula I have used in my own books, including the latest, King Richard: Nixon and Watergate — an American tragedy. In Six Months in 1945, I devoted several paragraphs to describing the lack of toilets at the Yalta conference, which forced delegates to relieve themselves beneath a statue of Lenin in the garden of the tsar's summer retreat. Some readers criticized me for that, but that's real life, the way delegates to the Yalta conference experienced it at the time. As one of them remarked in his diary, the toilet situation was the second most discussed subject at Yalta after World War II itself. So yes, I agree with Larson and Tolstoy that history is about the little people too... To coincide with the publication of my new book, King Richard, on Nixon and Watergate, I have compiled a list of the top five books for understanding why America's iconic political scandal happened. These are the books that were most helpful to me in my own research, as I tried to figure out the motivations of the principal characters.  1. Richard Nixon: The Life by John Farrell. In order to understand Watergate, you first have to understand Richard Nixon. This is the best, single-volume biography that chronicles Nixon's life in a balanced and fair way that gives us great insight into his character and motivations. Published in 2017, it is a model of its kind. Farrell attempts neither to vilify Nixon nor to defend him, but to explain him, in the context of his times. He gives us the extraordinary story of the self-made man from a struggling Quaker family in California who rose to the top through his own efforts - and then threw it all away through his own fatal flaws. Many of Nixon's gambles succeeded. Watergate was the one that failed.  2. The Haldeman Diaries by H.R. Haldeman. There was no one closer to Richard Nixon as Watergate unfolded than his chief of staff, Bob Haldeman. Every evening, Haldeman dictated an audio diary that is an essential source for understanding the Nixon presidency and the chain of events that led to its unraveling. While Haldeman admired Nixon, he was also well aware of his faults. He records the triumphs, failures, and personal quirks of his boss on an almost minute-to-minute basis. I think that Haldeman has it right when he concludes that Nixon did not know about Watergate in advance, in the sense that he did not order the break-in, but certainly caused it, in the sense that he created the culture that spawned all the abuses. Ultimately, these abuses led to Haldeman's own resignation and eighteen months in prison for Watergate-related offenses.  3. Will by G. Gordon Liddy. Gordon Liddy was an extraordinary character, a swaggering former FBI agent who was on a self-imposed mission to save America from "communism," even if it meant breaking the law. Even Nixon thought that Liddy was "a little nuts" but needed him as part of his campaign to get even with the Democrats and opponents of the war in Vietnam. In heading up the Watergate break-in, Liddy turned out to be a bungling amateur whose incompetence led directly to the failure of the operation. Nevertheless, he wrote one of the best books about Watergate--one that is both entertaining and revealing in its outrageous frankness and colorful descriptions of his fellow conspirators. A self-described admirer of Adolf Hitler, Liddy is a forerunner to the "patriots" who stormed Congress in January 2021 to "defend democracy." Liddy's 1996 autobiography is key to understanding the mentality that led to Watergate and continues to pose a threat to American democracy.  4. Blind Ambition by John Dean Dean's book is essential to understanding the psychodrama that led to the unraveling of the Watergate conspiracy. An ambitious lawyer picked to serve as White House counsel at the age of thirty-one, Dean feared that he was being set up to take the blame for Watergate. He was the first Nixon aide to appreciate the legal perils of the cover-up and the risks he was being asked to run. In order to save himself, he had to exit the conspiracy, betraying the president who was relying on him to throw a blanket over the scandal. In this 1976 memoir, Dean provides a candid account of his state of mind as he led a double life - Nixon loyalist by day, prosecution informant by night. Juggling the conflicting pressures, he began drinking ever more heavily, leading to a crisis in his marriage that provides a dramatic personal counterpoint to the crisis in the White House.  5. Abuse of Power by Stanley Kutler. Had Nixon not taped himself in secret, it is doubtful that he would have been forced to resign as president of the United States. While some of the most incriminating tapes were released as a result of a Supreme Court order, the remainder became the subject of a long legal tussle that continued for several decades. Nobody did more to secure the full release of the tapes than the historian Stanley Kutler who published highlights in his 1997 book, Abuse of Power. The tapes provide a unique insight into the functioning of the modern-day presidency, and Nixon's own personality, that is unlikely ever to be matched. Thanks to Kutler's efforts, we are able to hear Nixon in his own words and feel his pain and bewilderment as his world disintegrates around him. Whatever else you think of G. Gordon Liddy, the bungling Watergate mastermind who died this week, he was certainly a memorable character. As I wrote in an obituary of him that appeared on the front page of The Washington Post, even Richard Nixon thought he was "a little nuts." "I mean, he just isn't well-screwed on, is he," the president complained a week after the June 1972 break-in that sealed Liddy's place in history.

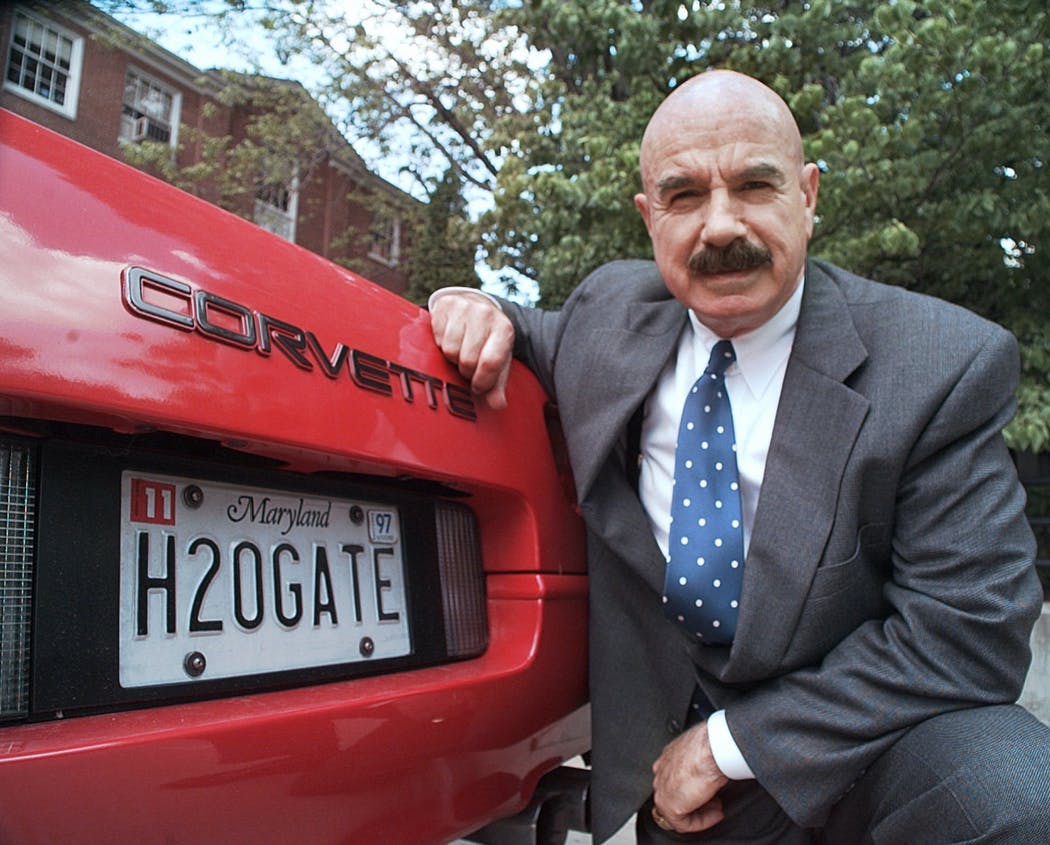

Liddy features prominently in my new book about Nixon and Watergate, King Richard: An American Tragedy, to be published on May 25 by Knopf. I describe how Liddy's combination of macho, can-do ruthlessness and ends-justify-the-means philosophy made him a natural fit for the Nixon era White House. Liddy may have been an unguided missile, but he was set in motion by a president who was determined to exact revenge on his political enemies. I was reminded of Liddy on January 6 when pro-Trump supporters invaded the Capitol in a failed bid to prevent the inauguration of Joe Biden. Like his latter-day imitators, Liddy believed that he was engaged in a war with the enemies of America--a category that included opponents of the Vietnam war, long-haired hippies and students, and their sympathizers in the Democratic party. From there, it became a short step to convince himself that he had a moral responsibility to do everything in his power to preserve his version of American greatness, whether or not his actions were legal. Liddy was a rogue, but an entertaining rogue. Despite all his considerable sins and faults, he wrote one of the best of the Watergate books. Titled Will, it sold more than a million copies. Even Bob Woodward, who certainly has no political sympathy for Liddy, praised the book for its honesty, describing its contents as "an embarrassment of riches" for Watergate aficianados. I acknowledge Liddy's book as an important source for King Richard, along with the extraordinary tapes bequeathed to us by Nixon. As a radio host who delighted in outraging the left, Liddy paved the way for the likes of Rush Limbaugh and even Donald Trump. He reveled in his celebrity, posing for photographs beside a succession of flashy sports cars with the personalized tag, H20GATE. He was the man the liberals loved to hate. RIP An American Original. It's always pleasant to discover an author much loved by others who you have managed to overlook yourself. I thank my parents for sharing their late life enthusiasm for the prolific Victorian novelist, Anthony Trollope. After they passed away, I spent a couple of years devouring the Trollope literary canon, beginning with his Chronicles of Barsetshire series about the vicious, back-biting politics of an English cathedral city, and moving on to his "political novels." For readers seeking an introduction to Trollope, I recommend starting with Barchester Towers. "You have before you one of the delights of life," wrote the economist John Kenneth Galbraith in a 1983 preface to the novel, explaining the attraction of Trollope for the John F. Kennedy set. (Students of the Cuban missile crisis will remember Kennedy's use of a "Trollope ploy"--the skillful exploitation of a romantic misunderstanding--to negotiate with Nikita Khrushchev, his opposite number in the Kremlin.) As Kennedy and other stressed-out politicians have discovered, a Trollope novel is a wonderful form of relaxation.

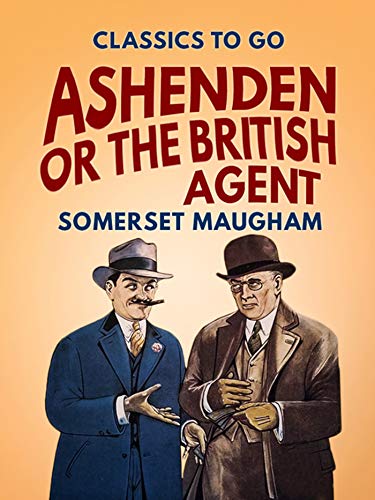

More recently, I have been binging on the novels and short stories of Somerset Maugham. I have just finished Of Human Bondage, (first published 1915) about uncontrollable passion, addiction, and unrequited love. It is widely considered Maugham's masterpiece, and includes many wonderful passages, but can be painful to read because of all the humiliations inflicted on the narrator. (Spoiler alert: he finds happiness in the end.) I actually preferred a much less celebrated book, Ashenden or the British Agent, (1927) which draws on Maugham's own experiences working for British intelligence in World War I in Switzerland and Russia. Connoisseurs of spy literature rightly credit Maugham with being the father of the modern espionage novel. Long before Graham Greene and John Le Carre, Maugham captured the everyday drudgery and moral equivocations of the spy business that is the complete opposite of the glamorous world depicted by the likes of Ian Fleming. The highlight of Ashenden, for me at least, were the chapters on Russia during the tumultuous period between the February and October 1917 revolutions. (Even though I am a student of Russian history, I had forgotten, or never knew, that Maugham was dispatched on a hopeless mission by American intelligence to try to keep Russia in the war.) I related to his experience on the Trans-Siberian railroad, "lost in the immensity of Russia and very lonely." There is a superb description of the British ambassador to Petrograd, Sir George Buchanan (disguised as "Sir Herbert Witherspoon"), as a coldly brilliant diplomat and epitome of the English aristocracy. Invited to dinner by the ambassador in his palatial residence, Ashenden/Maugham is "received with a politeness to which no exception could be taken, but with a frigidity that would have sent a little shiver down the spine of a polar bear." Although Maugham was one of the most widely read British authors of his day, he has been relegated to the second rank of English literature by snobbish critics. For me, however, his books are much more enjoyable than the dense "stream of consciousness" novels of writers like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf now regarded as literary classics. Spurned by the modernists as a literary hack and mediocre writer, Maugham created characters as unique and memorable in their own way as the characters of Charles Dickens. He had another quality too. Once you start a Maugham novel, you feel compelled to keep turning the pages until you reach the end. Feel free to disagree, but I certainly can't say that about the novels of Joyce or Woolf. I abandoned Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), generally regarded as much more "accessible" than Ulysses (1922), half-way through, and have had similar difficulty with both Mrs Dalloway (1925) and To The Lighthouse (1927). If readability is a measure of great literature, then surely Maugham deserves a place near the very top, along with his Victorian forebear, Anthony Trollope. I have just finished Educated, Tara Westover's remarkable memoir about growing up in a Mormon survivalist family in Idaho and the shock of discovering the strange new world beyond. It is the kind of book that can be read in many different ways, but here are a couple that resonated with me.

First, the writing style. Although Tara relates some horrifying experiences, including repeated episodes of physical abuse at the hands of an older brother, she refrains from explicitly passing judgment. As she explained in an interview with Jeff Goldberg of The Atlantic, she prefers "to stay in the moment" rather than "step outside and say what this means." This restraint has the paradoxical effect of making her writing more powerful and the message (however you choose to understand it) even more compelling. Instead of telling her readers what to think, she allows them to experience the horror that she endured and draw their own conclusions. It's a form of story-telling that I have tried to adopt in my own books, particularly the latest, King Richard (due out in May) which describes the Watergate scandal through the eyes of Richard Nixon and his senior advisors. Rather than condemn Nixon's criminal abuses of power, I attempt to give readers a worm's eye view of events inside the White House at the height of the scandal. I show how one bad decision leads inexorably to another, as the president attempts without success to escape from a spider web of lies and miscalculations of his own making. Like Tara, I strive to anchor the reader in the moment, curious to know what will happen next. Explicit moral judgments on the part of the author would only detract from the dramatic nature of the story. A non-fiction book or a novel can contain within it many different messages, even contradictory ones. One of my favorite novels growing up was A Many-Splendoured Thing by Han Suyin, about a love affair between a married British foreign correspondent and a Chinese doctor. It was later turned into a movie, Love is a Many-Splendored Thing (Note the British and American spellings!). Either way, it's a beautiful phrase that applies not just to love affairs--but to life itself, and therefore to literature. People remember the same events differently. There are several points in Educated where Tara acknowledges that her memory of certain traumatic events is at odds with the memories of other family members. Rather than insisting on the correctness of her version, she gives the reader several versions to choose from. It is a reminder that life does not proceed along straight lines, leading to neat conclusions. Instead it is messy and many-splendored, and the lessons we draw from life are messy and many-splendored as well. How you interpret a story often depends on the times in which you live. Educated came out at a time of growing political and cultural divisions in America--between the highly educated and the less educated, urban and rural, blue states and red states, people who have gained from the technological revolution and those who have lost out. Tara Westover is both a symbol of this division and the possibility of transcending it. She was essentially self-taught until the age of seventeen but, thanks to her own efforts and some inspiring teachers, went on to receive advanced degrees from top universities. She uses a term associated with the Salem witch trials--the "breaking of charity"--to describe a country in which half the population has lost nearly all connection with the other half. To travel from New York to rural Idaho is like traveling to a different country, with separate media universes, lifestyles, and belief systems. For my part, I am haunted by my experiences in Bosnia after the fratricidal war, investigating the massacre of 8,000 Muslims at Srebrenica by the Bosnian Serb army in July 1995. I frequently made the five-mile drive from Srebrenica (still predominantly Muslim) and Bratunac (largely Serb). Crossing the ethnic divide to conduct interviews on the rival sides was jarring. People who had grown up with each other, attended the same schools, and frequently inter-married now viewed each other as enemies. Each group had its own myths and truths, its own version of history, its own victims. There was little recognition, let alone empathy, for the suffering of the other side. It was a nightmare vision of where America could be headed--unless we find a way to bridge the cultural and economic gulfs that Tara Westover captures so well in Educated. As we celebrate the inauguration of Joseph Biden as the 46th president of the United States, a moment of gratitude is appropriate for our fellow Americans who made a transition of power possible. As a historian of presidential crises and chronicler of numerous coups and revolutions, I have compiled a top ten list of people who did their duty under some of the most trying circumstances imaginable. Since this is a purely personal selection, there is obviously plenty of room for debate.

First, a word of explanation about my choices. It may seem strange that there are more Republicans than Democrats on my list, even though Democrats have a much more consistent record of opposition to Trumpism. We must bear in mind, however, that it takes a lot more courage to go against your own party than to follow the party line. In resisting President Trump's attempts to overturn the 2020 election, Democrats were doing what was expected of them. Republicans who did the same thing were risking the anger of their base and even death threats. My list includes people with a history of supporting, and even enabling, our outgoing president. To those who believe that this disqualifies them from appreciation, I quote the wisdom of the gospel: "There shall be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who have no need of repentance." Defending the constitutional order is the responsibility of all Americans, not just a chosen few. That is why my list includes people from all walks of life, from high to low, from famous to obscure. They represent a wide gamut of American institutions--from the military to the media, from the judiciary to the world of sports. These institutions held because of individuals who showed up to work and did their job. Since we never know when we will be called upon to do our duty, it seems right to begin with one of these everyday heroes. 1. Capital Police officer Eugene Goodman. The sight of a lone black police officer facing down white rioters before diverting them away from the Senate chamber is likely to become one of the enduring images of the failed insurrection. He is a shining example of workplace courage. 2. U.S. District Court Judge Brett Ludwig. Tapped by Trump for the federal bench in early 2020, and approved unanimously by GOP senators, Ludwig upheld the results of the presidential election in Wisconsin. His ruling stated unambiguously that Trump was given "the chance to make his case and he has lost on the merits." 3. Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. The mild-mannered Republican withstood huge pressure to reverse the election, including a personal telephone call from the president urging him to produce 11,799 votes out of thin air. My favorite Raffensperger quote comes from his Jan. 2 phone call with Trump. "Well, Mr. President, the challenge that you have is that the data you have is wrong." A structural engineer, Raffensperger favored "the data" over political loyalty. That is the foundation of a free society. 4. Patriots Coach Bill Belichick. America's most celebrated football coach declined Trump's offer of the Presidential Medal of Freedom after the Capitol riots, citing the assault on "our nation's values, freedom, and democracy." By placing his civic duty above his friendship with Trump, he set an example that resonates far beyond professional sports. 5. Twitter boss Jack Dorsey. This is a tough one. The conflict-favoring algorithms of Twitter and other social media companies contributed greatly to the silo-ization of American politics, undermining our fact-based democracy. Dorsey tolerated the tweeter-in-chief for far too long before finally choosing to enforce his own rules against "incitement of violence." See Luke 15:7 above. 6. Fox News host Chris Wallace. A representative of the news media deserves inclusion on this list, but which one? By asking tough questions and speaking truth to power, while being fair to all sides, Wallace fulfilled his journalistic responsibilities honorably and honestly. The same could be said for many of his colleagues but Wallace stands out because he was working in the very belly of the Trumpist beast. 7. Former Defense Secretary James Mattis. The U.S. military is the ultimate guarantor of our freedom. When one of America's most respected generals reprimands the commander-in-chief for subverting the constitution, we need to pay attention. He deserves our gratitude for reminding everybody that our soldiers swear allegiance to the country, not to any individual. 8. Senator Mitt Romney. No GOP leader has been more consistent in standing up for democracy, and plain decency, than the failed 2012 presidential candidate. On the day of the insurrection at the Capitol, he urged his colleagues to tell voters "the truth": "President-elect Biden won this election, President Trump lost." 9. Outgoing Vice President Mike Pence. After four years of sycophancy and servility to Trump, the vice president performed his constitutional duty by certifying the results of 2020 election only hours after rioters had swarmed the Capitol chanting "Hang Mike Pence." He had no legal alternative but still merits our thanks for his call to Congress to "get back to work." 10. Incoming President Joe Biden. Through calm and steady leadership, the man that Trump called "Sleepy Joe" did more than anyone else to ensure a peaceful transition of power. By ignoring the temper tantrums and provocations of his predecessor, he charted a way to put the turmoil of the last four years behind us. He more than deserves his presidential honeymoon. I was recently back in the U.K., to visit my daughter in Scotland. We hiked to a lovely loch in the highlands, but storm clouds were gathering, and we came back drenched. A metaphor for Brexit!

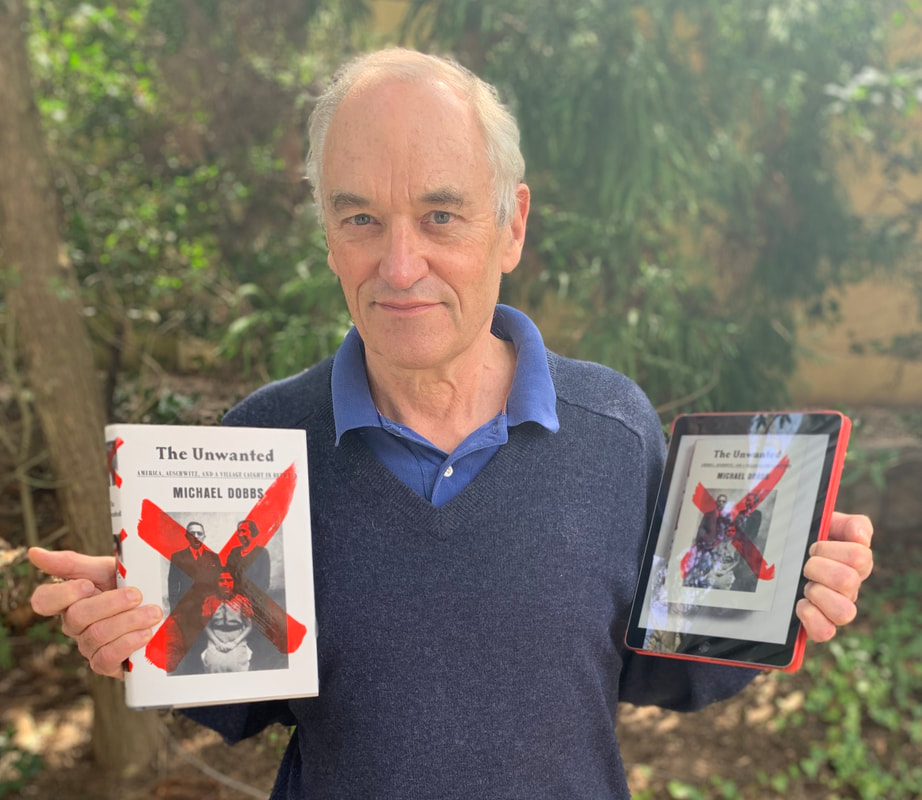

As an expatriate Brit who moved to the United States more than two decades ago, I have been trying to figure out the transformation that has overcome my native and adopted countries. Traditionally, we Anglo-Saxons have prided ourselves on our pragmatism and moderation. For decades, our systems of government were models for the rest of the world. Why have we suddenly become playgrounds for flag-waving nationalists, as exemplified by Donald Trump in the U.S. and Boris Johnson in Britain? Part of the answer, I think, lies in our curious, first past-the-post voting systems which makes it possible for an unpopular leader to take power without majority support, as long as he faces a divided opposition. The bottom line is that we do not vote directly for our leaders, either in the U.S. or in the U.K. Instead we have an electoral college mechanism that rewards conviction politicians who are able to pile up votes in the right places, but does not necessarily reflect the wishes of the majority of the population. I expand on these arguments in an op-ed piece that I wrote for The Washington Post, which you can find here. Even for the author of six books, there is still something magical about holding the finished product in your hands for the very first time. Today, I received advance copies of my latest opus, The Unwanted: America, Auschwitz, and a Village Caught in Between, which will be released on April 2. I hope you will agree that the publisher, Knopf, has done an exceptional job. This may be a slight exaggeration, but I think of Knopf (founded by Alfred A. Knopf and his wife Blanche in 1915) as the last of America’s “gentleman publishers.” They are a throwback to the age when editors treated writers with enormous courtesy, inviting them to long lunches and tolerating multi-year delays in the submission of manuscripts. They are also renowned for their gorgeously produced books. Even though Knopf is now part of a German-owned conglomerate, a Knopf book includes a number of design features, such as rough deckle edges and high quality paper, that make it easily recognizable. This time, as a special treat, I had the opportunity to see my book roll off the presses. Knopf books are printed in a small town in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia called Berryville, an hour’s drive from Washington D.C. where I live. It turns out that this charming, but otherwise insignificant town (population 4,185) is the location of one the largest printing operations in the United States, producing more than 10 million books a month. When I arrived, high-speed offset presses were churning out yet another reprint of Michelle Obama’s autobiography, Becoming, which has already sold some five million copies in the U.S. alone. In a different corner of the plant, my book was being printed in 32-page sections, known as “signatures,” which are most suitable for binding. In the photograph below, you can see the proud author holding a completed signature of The Unwanted, while a worker throws slightly imperfect versions into the trash. My main takeaway from my visit to Berryville was how old-fashioned the printing process remains. For all the technological advances of recent years, the basic techniques of book production are essentially little changed from the days of Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century. Ink is smeared onto paper through a mechanized process, and then bound into books with covers made out of pressed cardboard. The typefaces used in my book were designed by a Dutchman in the 17th century.

Like many of you, I suspect, I went through a phase of reading books on a Kindle or an I-Pad. But today, I greatly prefer the tactile sensation of handling a physical book. After many hours gazing into computer screens and smart phones, it is much more relaxing to curl up with a beautifully produced book than yet another electronic device. It is also much easier to move back and forth in a book, consulting an endnote or refreshing your memory about a character who has appeared in an earlier chapter. Six hundred years after its invention, the physical book is not only competitive with any of our modern technologies. With the possible exception of portability, it is superior in nearly every respect. In an age of bewildering change, that is immensely reassuring. |

About MichaelMichael Dobbs is the author of seven books, including the best-selling One Minute to Midnight. His latest book, King Richard, is about Nixon and Watergate. Archives

June 2021

|